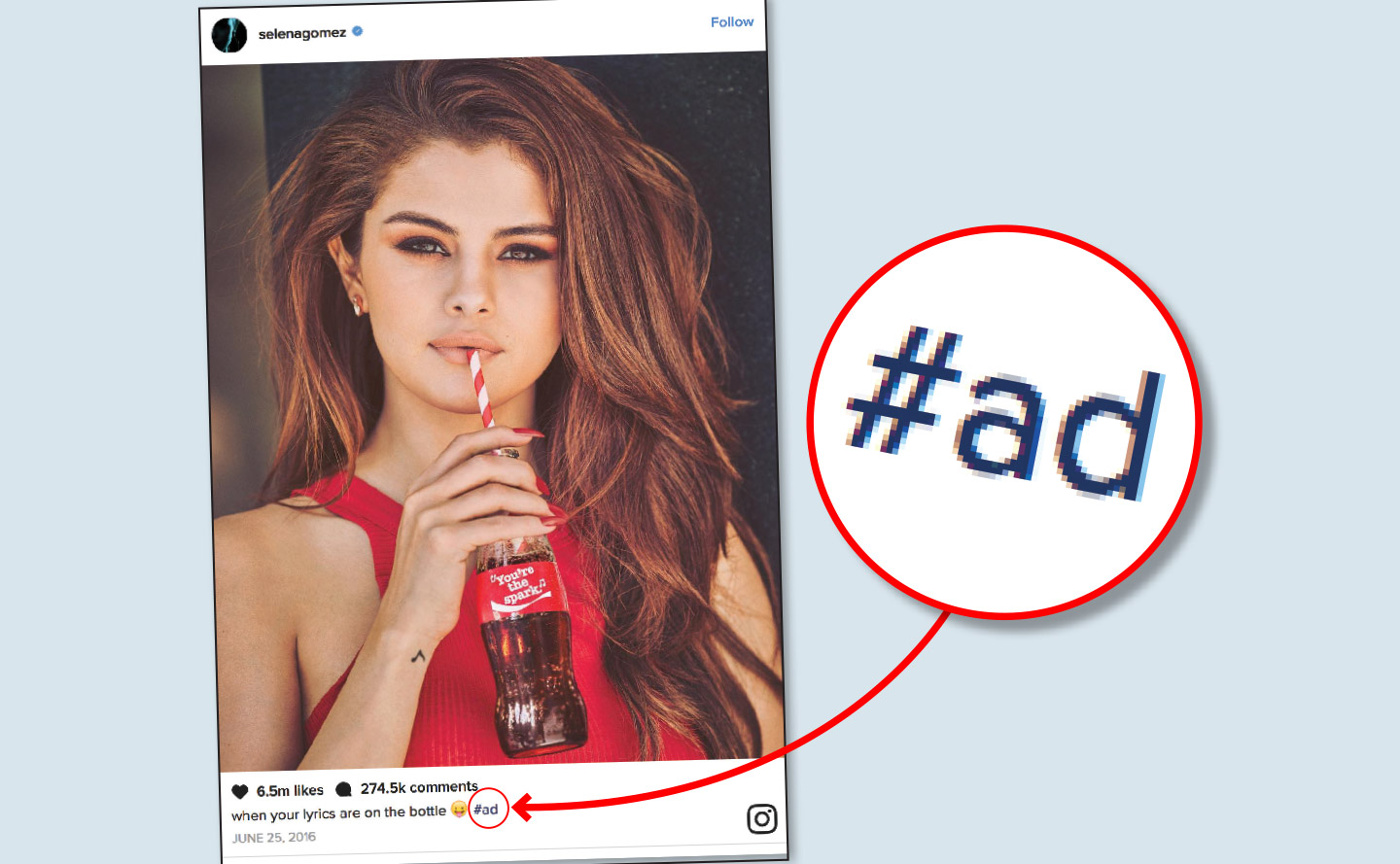

Last June, Selena Gomez posted a photo of herself drinking a bottle of Coke through a red-and-white striped straw on Instagram. “You’re the spark”—words from Gomez’s hit “Me & the Rhythm”—were visible on the label. Gomez added a caption: “When your lyrics are on the bottle.”

The photo, viewed by many of Gomez’s 112 million Instagram followers, is one of the most popular images in the social media platform’s history, with 6.5 million “likes” and more than 275,000 comments. Unlike some of the other photos Gomez posts, however, this one was a paid advertisement, and it spurred consumer advocates to take action.

TruthInAdvertising.org (TINA), a nonprofit group that monitors deceptive advertising, sent a letter to Coca-Cola, asking why the post wasn’t disclosed as an ad. After TINA’s complaint, the singer added the hashtag “#ad” to the post, which remains on her Instagram feed. (Gomez’s representatives didn’t return a request for comment.)

“If an individual has a material connection with the company, they are required to disclose that,” says Bonnie Patten of TINA. “The key here is transparency; it has to be clear if the content is advertising.”

This relatively new type of celebrity endorsement—and the ease with which the public can be fooled into viewing an unidentified ad—has federal regulators struggling to address the issue. Part of the problem is that long-standing rules, originally meant to regulate ads on TV and radio, aren’t so easily applied in today’s digital world.