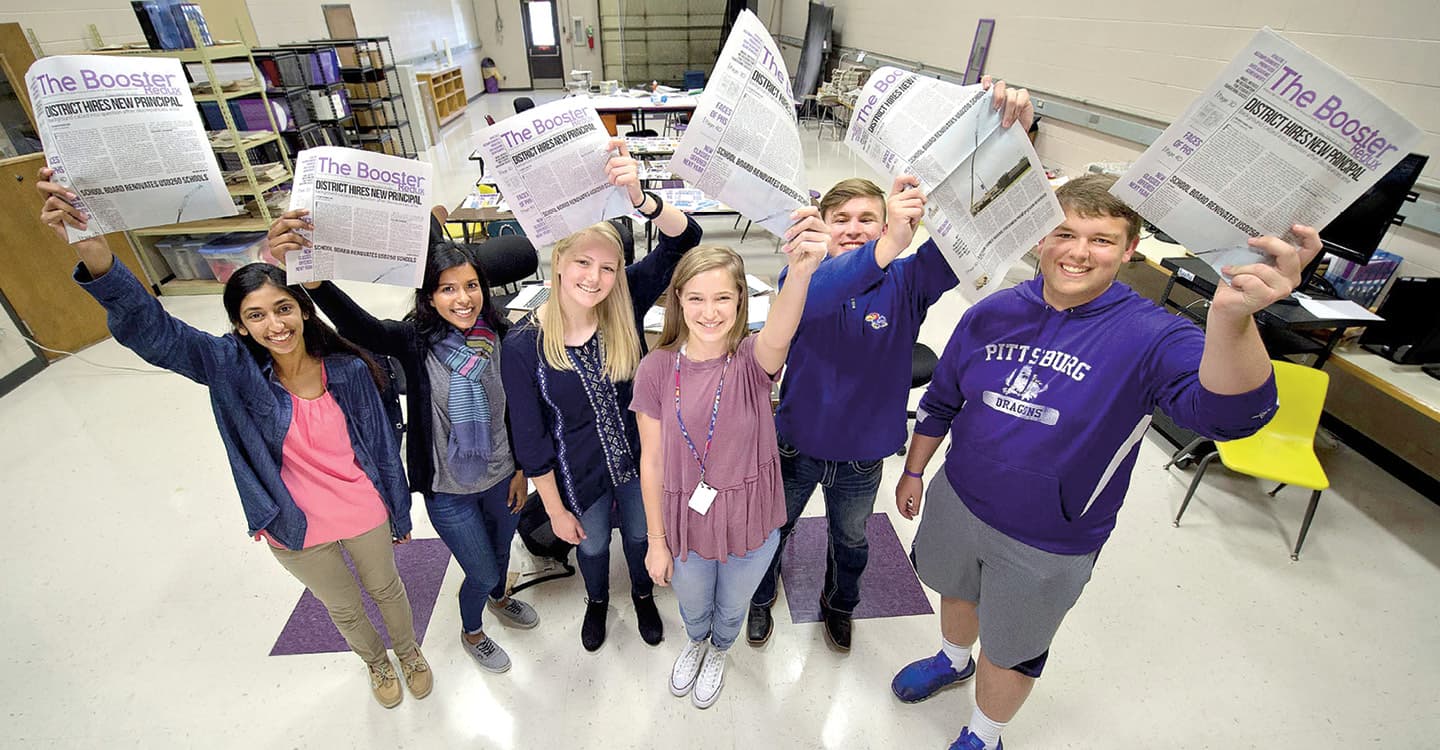

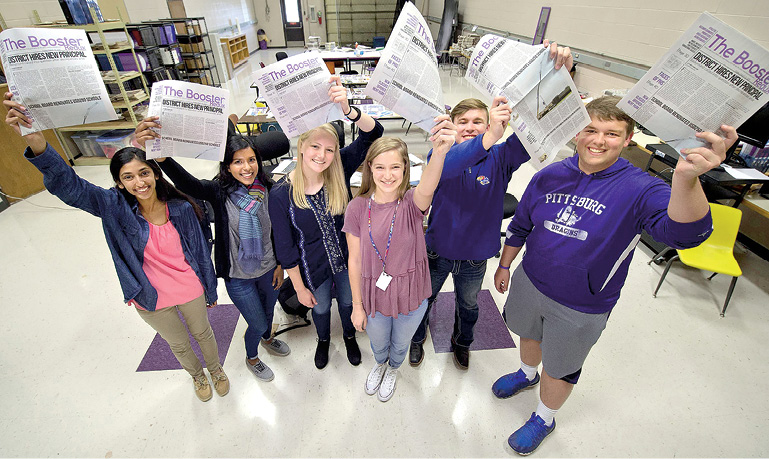

The student journalists at Pittsburg High School in Pittsburg, Kansas, were suspicious. They had set out to profile a recently hired principal, Amy Robertson, for the school paper—but the details of her background, including where she earned her degrees, didn’t add up.

The reporters met with superintendent Destry Brown about their concerns. He was supportive—so on a Friday night in March 2017, the paper published a story calling attention to the discrepancies. By Tuesday, Robertson had resigned “in the best interest of the district.”

Many praised the students. “I believe strongly in our kids questioning things and not believing things just because an adult told them,” Brown says.

The student journalists at Pittsburg High School in Pittsburg, Kansas, were suspicious. They had set out to profile a recently hired principal, Amy Robertson, for the school paper. But when they dug into her background, things didn’t add up. Even details like where she earned her degrees seemed questionable.

The reporters met with Superintendent Destry Brown about their concerns. He was supportive. So on a Friday night in March 2017, the paper published a story calling attention to the discrepancies. By Tuesday, Robertson had resigned “in the best interest of the district.”

Many praised the students. “I believe strongly in our kids questioning things and not believing things just because an adult told them,” Brown says.